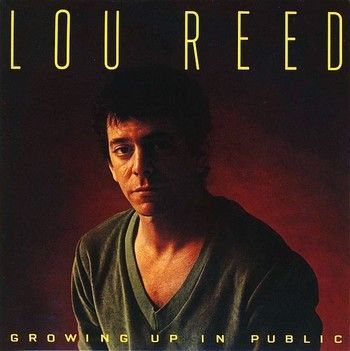

Lou Reed - Growing Up In Public - 1980 - Arista

The power of the Tower card come tumbling down, Growing Up In Public is the cartoon coloring book version of one man’s descent into the hell of the past. Similar to Alice Cooper’s From The Inside (another underrated favorite of mine), this album delivers a dire message in upbeat and almost childlike arrangements. It’s a deception, of course, and one need look no deeper than the groundbreaking guitar-synth work of Chuck Hammer to hear the lightning that rumbles Reed’s childhood fantasies. The opening “How Do You Speak To An Angel” is all polite and stuttering sweetness until the shocking guitar-synth solo comes crashing in, and you hear the rage underneath the impotence. The next track, “My Old Man,” reveals the source of that rage, and so begins a series of vignettes from a troubled childhood (“Smiles,” “Standing On Ceremony”) and ineffectual adulthood (“So Alone,” “The Power of Positive Drinking”). Yet, listening to this record, you’ll think Reed has gone soft. It’s the closest he’s come to making a pop album, with pleasant piano chords and bouncy bass guitar lines. The lyrics are another story; they talk of repression, anger and futility. The breakthrough moment occurs on “Think It Over,” when all of the bitterness is set aside for a shot at real love. In the interest of fair disclosure, I did own this on a cassette and played it in my car constantly, so familiarity may have bred fidelity. That would explain Tony Banks’ The Fugitive anyway. But I owned Street Hassle on cassette and that never got under my skin like Growing Up In Public. I certainly wouldn’t put Public on the same pedestal as Berlin, but song for song it’s one of the most likeable Lou Reed records I own; arguably the best of the comedic/tragic albums that would include Mistrial and Legendary Hearts. © 2009 Connolly & Company. All rights reserved http://www.connollyco.com/discography/lou_reed/growing.html

Check out lou Reed's classic "Coney Island Baby", "Sensations", and "Transformer" albums, and The Velvet Underground's brilliant "Loaded" album

TRACKS

1."How Do You Speak To An Angel?" – 4:08

2."My Old Man" – 3:15

3."Keep Away" – 3:31

4."Growing Up In Public" – 3:00

5."Standing On Ceremony" – 3:32

6."So Alone" – 4:05

7."Love Is Here to Stay" – 3:10

8."The Power Of Positive Drinking" – 2:13

9."Smiles" – 2:44

10."Think It Over" – 3:25

11."Teach The Gifted Children" – 3:20

All songs composed by Michael Fonfara & Lou Reed

MUSICIANS

Lou Reed: guitar, vocals

Michael Fonfara: keyboards, guitar

Chuck Hammer: guitar, guitar synthesizer

Stuart Heinrich: guitar, background vocals

Ellard "Moose" Boles: bass, background vocals

Michael Suchorsky: drums

REVIEWS

Aw, not too good. A lot of life philosophy, which may or may not speak to you, and a definite lack of care for the music. Best song: THE POWER OF POSITIVE DRINKING

Track listing: 1) How Do You Speak To An Angel; 2) My OId Man; 3) Keep Away; 4) Growing Up In Public; 5) Standing On Ceremony; 6) So Alone; 7) Love Is Here To Stay; 8) The Power Of Positive Drinking; 9) Smiles; 10) Think It Over; 11) Teach The Gifted Children.

Lou entered the Eighties completely 'ready to suck', as might be said. It's not that he was being misled by robotic, technophilic production, a thing all too common for elder stars in the decade; it's just that it was much and much too hard for him to remain on the leading edge of musical innovation. Just take a look at this record. You might notice these hardly impressive numbers that I put up there in the beginning and think that I completely condemn this album as a rotten one or something. Actually, not at all: I don't really mind listening to this stuff, just as I don't really mind listening to, say, Bob Dylan's contemporary stuff (although he did release his worst album ever that year). It's fairly decently produced, too - the band is stripped down once again, with the main emphasis on a couple electric guitars and the rhythm section, and only Michael Fonfara's annoying synths manage to spoil the picture from time to time. Plus, the record is not too long: eleven cuts, none of which go over four minutes, so if you don't like a song, chances are it'll go away before you even have the chance to express your disappointment. The problem is, there's hardly a good song here you'll like in all. And a major problem it is, as the tracks on this record hardly even fit the definition of 'song'. Much more often, it's just pieces of entertaining or not that enetertaining monolog set to a certain musical backing. 'So what's the deal?', you'll say. 'It's Lou's usual approach - mumbling out his life philosophy to some musical backing or other.' True, of course, but there comes a time, every now and then, when the formula begins to get on your nerves, especially when there are next to no musical ideas at all to back it. In the past, Lou used spare arrangements as well, but he always managed to make them moody and enthralling enough to fit in with the words and the overall message. On Growing Up In Public, the music seems kinda... in the way, if you know what I mean. In the way of 'poetry'. I can easily imagine this album not having any music at all - you know, just 'Lou Reed-ing Poetry'. No cool vocal harmonies here, no delicious slide guitar, no lounge trumpets, no impressive guitar solos; like I said, the only musically significant element here are Michael Fonfara's synthesizers which mostly stay in the background but sometimes get into the spotlight a bit too much and give the song an ultra-banal Eighties' feel which it really does not need at all, as in the case of the pathetic instrumental break on 'How Do You Speak To An Angel'. Growing Up In Public is basically a concept album (big surprise) about, well, growing up, whether it be in public or not. Thus, it happens to contain more than a fair share of autobiographic songs, rendering it perhaps the most important self-describing album in Lou's career. The more personal song thematics range from first youth reminiscences ('How Do You Speak To An Angel') to rough parental relations ('My Old Man') to problems with establishing social contact (title track) and, well, the themes are many and they're not all that unusual for an autobiographical cycle. The lyrics are also nothing really special: 'My Old Man' even borders on banal, if not for the somewhat unexpected ending. I mean, most of this stuff is nice, but then again, so are hamburgers. I'd come to expect something more deep and thought-provoking from Lou: this autobiographical cycle is to, say, Coney Island Baby as the Kinks' later obnoxious rock operas are to their early deeply intelligent and sharp concept albums. On this here record Lou is probably at his best when the songs are quiet and relaxed; my favourite is the pleasant little reggae-ish shuffle 'The Power Of Positive Drinking'. It might feel out of place on the album, as it's essentially a funny throwaway - come on now, how come a song with lyrics like 'Some say liquor kills the cells in your head/And for that matter so does getting out of bed' belongs on here? But I love it all the same. Then there's 'Teach The Gifted Children' which (a) closes the album (so you're particularly grateful to it), (b) clocks in at 3:20 (so you're able to breathe with relief), (c) has by far the most interesting lyrics on the album (so you say: 'He's smart! He kept the best bit for the end!'), and (d) tries to sound very emotional and climactic and maybe even cathartic, but fails, because the message is definitely unclear (what's the whole business with 'take me to the river' really about?) and the musical backing is monotonous and boring. So you say: 'Yeah, he's a genius, but he sucks!' None the more so than on the faster numbers, though - 'Smiles' and 'So Alone' just bug me, especially the latter where Lou gets extremely hoarse and implores you to 'shake your booty' in that exact intonation. Nah. The only other tracks which I can remind as possessing interesting moments are the title track, that had a strange trumpet-imitating synth riff over it, kinda reminding you of the old Transformer days, and the already mentioned 'How Do You Speak...' with its weird time changes and twisted refrains. Everything else is simply forgettable - take Coney Island Baby, substitute all the subtle instrumentation and romantic mood with emotionless, noodling generic guitars and dreary whining and you get Growing Up. Forgettable. Whew. Don't believe me? Just take a look at the album cover for CIB and this one. See the difference? Same goes for the music. © Only Solitaire - George Starostin's Music Reviews © http://starling.rinet.ru/music/reed.htm#Public

Growing Up in Public was a transitional album for Lou Reed; it was his last set with his long-running road band (dominated by keyboardist Michael Fonfara), and while the fleshed-out arrangements are of a piece with Reed's work on Rock & Roll Heart and The Bells, the lyrics of the best songs anticipate the directly personal, emotionally naked songwriting that marked the two extraordinary albums that would follow, The Blue Mask and Legendary Hearts. "How Do You Speak to an Angel," "My Old Man," and "Standing on Ceremony" deal with Reed's family issues with a direct force he hadn't summoned since "Kill Your Sons" (we'll leave it to others to debate their accuracy), and "So Alone" and "Keep Away" both offer a trenchant but heart-rending look at modern relationships. And "The Power of Positive Drinking" is amusing, but rather surprising coming from a guy who would give up alcohol and drugs a year after this was released. Growing Up in Public didn't get much notice on its initial release, but all these years later it sounds like a dry run for what was to be the most creatively fruitful period of Lou Reed's solo career. © Mark Deming © 2010 Rovi Corporation. All Rights Reserved http://www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&sql=10:etanqj6bojda

BIO

The career of Lou Reed defies capsule summarization. Like David Bowie (whom Reed directly inspired in many ways), he has made over his image many times, mutating from theatrical glam rocker to scary-looking junkie to avant-garde noiseman to straight rock & roller to your average guy. A firmer grasp of rock's earthier qualities has ensured a more consistent career path than Bowie's, particularly in his latter years. Yet his catalog is extremely inconsistent, in both quality and stylistic orientation. Liking one Lou Reed LP, or several, or all of the ones he did in a particular era, is no guarantee that you'll like all of them, or even most of them. Few would deny Reed's immense importance and considerable achievements, however. As has often been written, he expanded the vocabulary of rock & roll lyrics into the previously forbidden territory of kinky sex, drug use (and abuse), decadence, transvestites, homosexuality, and suicidal depression. As has been pointed out less often, he remained (and remains) committed to using rock & roll as a forum for literary, mature expression well into middle age, without growing lyrically soft or musically complacent. By and large, he's taken on these challenging duties with uncompromising honesty and a high degree of realism. For these reasons, he's often cited as punk's most important ancestor. It's often overlooked, though, that he's equally skilled at celebrating romantic joy, and rock & roll itself, as he is at depicting harrowing urban realities. Although Reed achieved his greatest success as a solo artist, his most enduring accomplishments were as the leader of the Velvet Underground in the '60s. If Reed had never made any solo records, his work as the principal lead singer and songwriter for the Velvets would have still ensured his stature as one of the greatest rock visionaries of all time. The Velvet Underground are discussed at great length in many other sources, but it's sufficient to note that the four studio albums they recorded with Reed at the helm are essential listening, as is much of their live and extraneous material. "Heroin," "Sister Ray," "Sweet Jane," "Rock and Roll," "Venus in Furs," "All Tomorrow's Parties," "What Goes On," and "Lisa Says" are just the most famous classics that Reed wrote and sang for the group. As innovative as the Velvets were at breaking lyrical and instrumental taboos with their crunching experimental rock, they were unappreciated in their lifetime. Five years of little commercial success was undoubtedly a factor in Reed leaving the group he had founded in August 1970, just before the release of their most accessible effort, Loaded. Although Reed's songs and streetwise, sing-speak vocals dominated the Velvets, he was perhaps more reliant upon his talented collaborators than he realized, or is even willing to admit to this day. The most talented of these associates was John Cale, who was apparently fired by Reed in 1968 after the Velvets' second album (although the pair have worked together on various other projects since then). Reed has a reputation of being a difficult man to work with for an extended period, and that has made it difficult for his extensive solo oeuvre to compete with the standards of brilliance set by the Velvets. Nowhere was this more apparent than on his self-titled solo debut from 1971, recorded after he'd taken an extended hiatus from music, moving back to his parents' suburban Long Island home at one point. Lou Reed mostly consisted of flaccid versions of songs dating back to the Velvet days, and he could have really used the group to punch them up, as the many outtake versions of these tunes that he actually recorded with the Velvet Underground (some of which didn't surface until about 25 years later) prove. Reed got a shot in the arm (no distasteful pun intended) when David Bowie and Mick Ronson produced his second album, Transformer. A more energetic set that betrayed the influence of glam rock, it also included his sole Top 20 hit, "Walk on the Wild Side," and other good songs like "Vicious" and "Satellite of Love." It also made him a star in Britain, which was quick to appreciate the influence Reed had exerted on Bowie and other glam rockers. Reed went into more serious territory on Berlin (1973), its sweet orchestral production coating lyrical messages of despair and suicide. In some ways Reed's most ambitious and impressive solo effort, it was accorded a vituperative reception by critics in no mood for a nonstop bummer (however elegantly executed). Unbelievably, in retrospect, it made the Top Ten in Britain, though it flopped stateside. Having been given a cold shoulder for some of his most serious (if chilling) work, Reed apparently decided he was going to give the public what it wanted. He had guitarists Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner (who had already played on Berlin) give his music a pop-metal, more radio-friendly sheen. More disturbingly, he decided to play up to the cartoon junkie role that some in his audience seemed eager to assign to him. On-stage, that meant shocking bleached hair, painted fingernails, and simulated drug injections. On record, it led to some of his most careless performances. One of these, the 1974 album Sally Can't Dance, was also his most commercially successful, reaching the Top Ten, thus confirming both Reed's and the audience's worst instincts. As if to prove he could still be as uncompromising as anyone, he unleashed the double album Metal Machine Music, a nonstop assault of unlistenable electronic noise. Opinions remain divided as to whether it was an artistic statement, a contract quota-filler, or a slap in the face of the public. While Reed has never behaved as outrageously (in public and in the studio) as he did in the mid-'70s, there was plenty of excitement in the decades that followed. When he decided to play it relatively straight, sincere, and hard-nosed, he could produce affecting work in the spirit of his best vintage material (parts of Coney Island Baby and Street Hassle). At other points, he seemed not to be putting too much effort into any aspect of his songs ("Rock and Roll Heart"). With 1978's Take No Prisoners, he delivered one of the weirdest concert albums of all time, more of a comedy monologue (which not too many people laughed hard at) than a musical document. Reed had always been an enigma, but no one questioned the serious intent of his work with the Velvet Underground. As a soloist, it was getting impossible to tell when he was serious, or whether he even wished to be taken seriously anymore. At the end of the '70s, The Bells set the tone for most of his future work. Reed would settle down; he would play it straight; he would address serious, adult concerns, including heterosexual romance, with sincerity. Not a bad idea, but though the albums that followed were much more consistent in tone, they remained erratic in quality and, worse, could occasionally be quite boring. The recruitment of Robert Quine as lead guitarist helped, and The Blue Mask (1982) and New Sensations (1984) were fairly successful, although in retrospect they didn't deserve the raves they received from some critics at the time. Quine, however, would also find Reed too difficult to work with for an extended period. New York (1989) heralded both a commercial and critical renaissance for Reed, and in truth it was his best work in quite some time, although it didn't break any major stylistic ground. Reed works best when faced with a challenge, which arrived when he collaborated with former partner John Cale in 1990 on a song cycle for the recently deceased Andy Warhol. In both its recorded and stage incarnations, this was the most experimental work that Reed had devised in quite some time. Magic and Loss (1992) returned him to the more familiar straight rock territory of New York, again to critical raves. The re-formation of the Velvet Underground for a 1993 European live tour could not be considered an unqualified success, however. European audiences were thrilled to see the legends in person, but critical reaction to the shows was mixed, and critical reaction to the live record was tepid. More distressingly, old conflicts reared their head within the band once again, and the reunion ended before it had a chance to get to America. Cale and Reed at this point seem determined never to work with each other again (the death of Velvet Underground guitarist Sterling Morrison in 1995 seemed to permanently ice prospects of more VU projects). In 1996, the surviving Velvet Underground members were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, performing a newly penned song for their fallen comrade, Morrison. Reed closed the '90s with an album that saw him explore relationships, 1996's Set the Twilight Reeling (many speculated that the album was biographical and focused on his union with performance artist Laurie Anderson), which didn't turned out to be one of Reed's more critically acclaimed releases. He also found time to compose music for the Robert Wilson opera Timerocker, and in 1998, released the "unplugged" album Perfect Night: Live in London. The same year, Reed was the subject of a superb installment of the PBS American Masters series that chronicled his entire career (eventually released as a DVD, titled Rock and Roll Heart). 2000 saw Reed's first release for Reprise Records, Ecstasy, a glorious return to raw and straightforward rock, a tour de force that many agreed was his finest work since New York. Another collaboration with Robert Wilson, POE-try, followed in 2001 and continued its worldwide stage run through the year. Including new music by Reed and words adapted from the macabre texts of Edgar Allan Poe, POE-try led to Reed's highly ambitious next album, The Raven. Animal Serenade, a double-disc set recorded at the Wiltern Theater in Los Angeles during his 2003 world tour, was issued in spring 2004. The live effort is Reed's tribute of sorts to his celebrated Rock N Roll Animal concert album, which was released 30 years before. In 2007 Reed released Hudson River Wind Meditations, a four-song experimental sound collage that celebrated both the best and worst aspects of Metal Machine Music. Reed's solo work ultimately cannot stack up to his Velvet output, despite its many highlights. Still, most would have to concede that with the exception of Neil Young, no other star that rose to fame in the '60s has continued to push himself so diligently into creating work that is meaningful and contemporary. If that means he relies on stock musical and lyrical ideas at times (as Young does), it also means he's proved that rock can remain relevant to listeners other than hormone-crazed teenagers. © Richie Unterberger & Greg Prato © 2010 Rovi Corporation. All Rights Reserved http://www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&sql=11:0ifrxqr5ldje~T1