Bill Connors' great moment of fame occurred when he was with Chick Corea's Return to Forever during 1973-1974, recording the influential Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy. His decision to leave RTF to concentrate more on acoustic guitar may have been satisfying artistically, but it cut short any chance he had at commercial success. Previously, he had played electric guitar with Mike Nock and Steve Swallow in San Francisco; but his post-1974 work was primarily acoustic, particularly in the 1970s when he recorded a series of atmospheric albums for ECM (including with Jan Garbarek). In the mid-'80s, for Pathfinder, Connors' music became more rock-oriented, but those releases did not make much of an impact despite his talent. © Scott Yanow © 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. | All Rights Reserved http://www.allmusic.com/artist/bill-connors-mn0000070942/biography

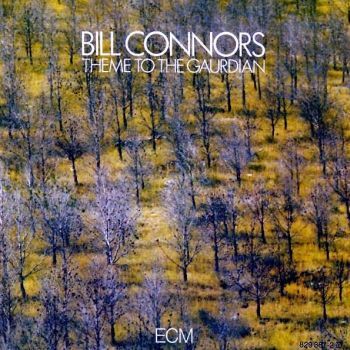

The blazingly explosive and technically precise legato guitarist in Return to Forever left after one release with RTF to pursue a solo career and much quieter, acoustic guitar path. This is the first in a trio of acoustic guitar releases Connors put out in the '70s on the famous ECM label. Theme to the Guardian features some truly excellent acoustic guitar work, with some unique compositions and playing styles. Connors dubs one track as a sort of complex and exotic chordal progression-based structure of strummed rhythms and/or a tapestry of three-finger rolling. Connors solos over this landscape of dreamy, moody, surreal, and frenetic design. The effect is a ghostly dance of melancholy angst and passionate wailings. © John W. Patterson © 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. | All Rights Reserved http://www.allmusic.com/album/theme-to-the-guardian-mw0000197363

Great innovative acoustic guitar based jazz fusion album from one of the best guitarists you may never have heard! The chords, melodies,and song structures are ahead of their time. This subtle and beautiful album is just as enjoyable as any full blown aggressive electric fusion album with a full band. HR by A.O.O.F.C. Listen to Bill’s “Return” album, and check out Bill’s “Double Up”,” “Step It”, “Assembler”, and “Swimming With A Hole In My Body” albums on this blog. Listen to the late Emily Remler’s “Firefly” album sometime. [All tracks @ 320 Kbps: File size = 105 Mb]

TRACKS

1 Theme To The Gaurdian 5:15

2 Childs Eyes 4:22

3 Song For A Crow 4:13

4 Sad Hero 4:25

5 Sea Song 5:00

6 Frantic Desire 2:52

7 Folk Song 6:32

8 My Favorite Fantasy 4:23

9 The Highest Mountain 3:24

All tracks composed by Bill Connors except Track 5 composed by Glenn Cronkhite

BIO (WIKI)

Bill Connors (born September 24, 1949) is an American jazz musician notable for being a legato technique master, adept at both the acoustic and electric guitar, and successfully played jazz-rock, free and fusion material in the '70s and '80s. His best early solos were in the jazz-rock genre, where his use of distortion and electronics was balanced by fine phrasing and intelligent solos. His first great moment of fame occurred when he joined Chick Corea's Return to Forever in 1973, recording Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy, though he quit in 1974 and was followed by Earl Klugh, who was then replaced by Al Di Meola. His decision to leave Return to Forever to concentrate more on acoustic guitar was satisfying artistically: he recorded three acoustic albums and then three electric albums as a leader/soloist, and recorded and performed with others. The quality, innovation and thoughtfulness of his work has always garnered strong praise. Connors was born in Los Angeles, California in 1949 and began to play the guitar at the age of fourteen. After three years of extensive self-study of the rock and blues influences that were his first inspiration, he began to play gigs around the Los Angeles area. He soon found his way to jazz, the music that would lead to a lifelong commitment. "I'd been playing for about four years", he explained at the time of his RTF tenure, "and suddenly had an overnight change. I didn't want to be a blues guitarist anymore. I began listening to people like Bill Evans, Jim Hall, Wes Montgomery, [bassist] Scott LaFaro, Miles Davis, [John] Coltrane—anyone who had a 'jazz' label. Django Reinhardt really got to me. The first time I heard one of his records, I thought that was just what I wanted to be. He had all the fire, creativity, and energy that rock players have today. And the amazing purity of his melodies—you just knew they came from a totally instinctive place." He and Django differed however over the matter of electronics with Bill preferring the sound of the electric instrument. "I always wanted to use the electric guitar in a sophisticated context, like with Chick [Corea]. I like to play jazz with that electric-rock sound. For me it's a lot closer to a horn than the traditional guitar, and that's what I love about it; I can sustain notes, get into different kinds of phrasing -- do things other instruments do naturally, only the guitar does it with the aid of technology." Connors moved to San Francisco in 1972 to join the Mike Nock Group (formerly known as "The Fourth Way") with drummer Eddie Marshall and bassist Dennis Parker. He met up with drummer and vibraphonist Glenn Cronkhite, who would introduce him to a new depth of jazz sounds and study. In those early years in the city by the bay, Connors played with numerous top-flight musicians, including Cronkhite, bassist Steve Swallow and pianist Art Lande. In 1973, after sitting in on a gig, Connors was signed on to Return to Forever, keyboardist and composer Chick Corea’s pioneering fusion group that featured bassist Stanley Clarke and (then) drummer Steve Gadd. "A miracle!" Bill claims. "Chick was my hero. I wanted to be Chick Corea on guitar. I didn't know him, but whenever I really wanted to get off on music I'd play some of his piano solos and Return To Forever songs. I heard that Chick was looking for a guitarist. Steve encouraged me to call Chick, and though I was very nervous, I did, and he invited me to come over to the club where he was working and sit in. I was so scared that I almost turned him down. But after running around and saying to everyone, 'Guess who I'm going to play with tonight,' and everyone telling everyone else, all this energy was formulating—and I took to my room and practiced my ass off." That night, the fright totally disappeared. "The minute I got up on stage I had this feeling like I'd been preparing for this all my life. I was so relaxed that I felt as though I was in my own living room. Chick and I played musical games -- he'd play these real simple lines and I'd be giving my interpretations of them, then go off into the Chick Corea 'outness.' I ended up in New York two weeks later." With keyboardist and composer Chick Corea’s pioneering fusion group that featured bassist Stanley Clarke and drummer Lenny White, Connors established himself on the national and international music scenes, touring in Japan and Europe, and recording the now legendary Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy. Connors' playing with the group and on Hymn... spearheaded an unprecedented direction for guitar in jazz. "It's hard to overlook the early Return to Forever or the Stanley Clarke debut solo recording, but.. again sentiment has taken over...but here is truly the FIRST guitarist to play fusion with a KILLER 'rock' guitar sound". - Steve Kahn. But there is often a problem when wishes come true; in April 1974, after the band's tour of Europe and Japan, Bill quit the group. The musical direction seemed to him to be changing from what it was when Connors joined. He explains, "Everything started getting less aesthetic, more rock. Just too much like Mahavishnu (John McLaughlin (musician)). I was having trouble expressing myself the way I wanted to in that context." Connor's disenchantment with the group also stemmed from certain objections to Corea's Scientology-inspired leadership style. "Chick had a lot of ideas that were part of his involvement with Scientology. He got more demanding, and I wasn't allowed to control my own solos. I had no power in the music at all. Then, we'd receive written forms about what clothes we could wear, and graphic charts where we had to rate ourselves every night – not by our standards, but his. Finally, we had to connect dots on a chart every night. I took all of it seriously because I had a lot of respect for Chick, but eventually I just felt screwed around. In the end, my only power was to quit." In 1974, Connors left RTF, and began to explore the New York jazz and session scene, performing with guitarist John Abercrombie and keyboardist Jan Hammer, and recording with bassist Stanley Clarke. "It was great,"he states, "because it wasn't this contrived thing in order to communicate to the audience. We were *playing* again and *learning* again, and it felt real good." During this period, record dates with artists as diverse as vocalist Gene McDaniels and Stanley Clarke kept the guitarist's creative impulses occupied with a variety of challenges—but not for long. "Around 1975, I'd decided to become a classical guitar player", he muses. "I did my first solo album in 1974, and just decided on the spur of the moment to do it all on acoustic. That was just such a contrast from blowing people's ears off with my 200-watt Marshall that it really started to capture me." A further impetus came with Connors' discovery of classical artist Julian Bream. "I was sitting with his album 20th Century Guitar [RCA, LSC2964] -- a real classic -- and it has this piece by [German composer] Henze that I really loved. It was just getting to me, so I sat down for a couple of days and transcribed it -- on my steel-string guitar, with my funny pick-and-finger technique [laughs]. When I got it, it gave me so much pleasure that I said, 'Okay, I'm going to be a classical guitar player.' And that's what happened." "I bought a bunch of books and a classical guitar, and started with the C scale, playing 'i m i m' [index, middle, index, middle], etc. For about three years, I practiced eight hours a day: up early, play for five hours, take a break, and play for three more hours. I'd throw in some extra hours if I could. My reading sure improved after that. You've got to understand that I come from an unschooled background—all my schooling is self-inflicted [laughs]. I like scales, technique, and intelligence, but they weren't natural for me. Being a blues player was natural for me, but it wasn't enough." Connors recorded his first solo album in 1974, Theme to the Guardian (ECM), making the switch from electric to acoustic guitar. At the same time, he began the next phase of his self-driven studies, taking it on himself to delve into transcriptions and studies of the works of classical guitarists. Two more recordings on acoustic guitar followed, 1977's Of Mist and Melting (ECM), with Connors as leader and on guitar, saxophonist Jan Garbarek, bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Jack DeJohnette and then, in 1979, another solo effort by the guitarist, Swimming with a Hole in My Body (ECM). During 1976 and 1977, Connors also recorded with Lee Konitz, Paul Bley and Jimmy Giuffre in New York. He toured Europe, performing with composers Luciano Berio and Cathy Berberian. Connors then returned to electric guitar, performing and recording with Jan Garbarek on Places (1978) and Photo with Blue Sky, White Cloud, Wires, Windows and a Red Roof (1979), and with Tom Van Der Geld and Richard Jannotta in 1979 (Path, ECM). In 1985, Connors recorded Step It (Pathfinder/Evidence), featuring Connors and Steve Kahn on guitars, Tom Kennedy on bass and Dave Weckl on drums. Music critic Gene Santoro said of Connors’ playing on the album: “the aching blues phrases sing with the expressiveness of early-to middle-period Clapton; the sudden note blizzards strike with the stark power of a John Coltrane sax solo ” (Guitar Player, May 1985). Connors’ next album, 1986's Double Up, again featuring bassist Kennedy but now with drummer Kim Plainfield, brought more accolades: “Connors is back, stronger than ever with one of the most dynamic, burning sounds in electric jazz” and “Connors soars, smolders, and screams; don’t miss it” (Jim Ferguson, Guitar Player, April 1987). The same trio (Connors, Kennedy, Plainfield) recorded Assembler in 1987, and again reviewers praised the sounds: “Connors’ flowing, passionate lines in the context of slippery, interactive funk grooves laid down by drummer Plainfield, a master of slick time displacement, and the accomplished 6-string electric bassist Tom Kennedy...the three reach a special accord... Bill Connors is in rare and ripping form” (reviewer Bill Milkowski). For the past years, Connors has been giving private lessons while continuing his stylistic and technical studies of the works of jazz greats. He’s now playing plectrum style on a classical jazz guitar, an archtop electric. Connors is a mature professional with a highly polished level of musicianship, a sure sense of direction, and the same overriding love for the music that has always been his touchstone. Recent press continues to praise Connors' work, his contributions to the field of music, and his continued innovations: "Bill Connors was the 'cry of love' in jazz/fusion guitar. He may be the most misunderstood, overlooked, and maligned character on the scene at the time" (Vernon Reid, notes to Columbia/Legacy box set 100 Years of Jazz Guitar). The following selection speaks to Connors' 2005 release, Return: "Bill Connors has always lived and played ahead of the times...... masterful playing and infectious grooves... If Connors' past albums can be likened to swimming in a pool at an all-night pool party, then Return is like taking a dive into the open sea... The band is so tight that much of the record sounds like a duet, with bass, drums, and percussion forming a singular rhythmic landscape for the piano and guitar to dance through like light beaming into a raindrop... All in all, Return is a mature and playful album. The musicians are responsive and fluid, in complete control of the music, and are unafraid to lead the listener into uncharted territory" (Ari Messer, June 2005, Guitar Player). "Playing a mellow-toned Gibson L5 through his own hand-crafted amp, Connors is an emotional, sophisticated and subtle soloist to go with flawless technique..." (Los Angeles Daily Times, February 2005). "Connors' perfectionism is evident... throughout,his tone is round and penetrating, considerably weightier than the typical jazz guitar sound; his technique, meanwhile, is flawless, his lines totally logical" (Adam Perlmutter, Guitar One). "The first thing that hits you about this record is the songs. They are memorable and sound great... The next thing that hits you is Bill's playing... a take on Coltrane's "Brasilia" is pure heaven. The ballad lets Connors demonstrate some haunting, bluesy, soulful playing that is, in a word, gorgeous" (John Heidt, Vintage Guitar). "Connors’ line of attack on Return is centered upon his supple, fingerstyle picking and clean jazz licks, augmented by a resplendent, medium-toned electric sound. He uses space as an effective vehicle, whether alternating between buzzing single-note runs or when improvising through a primary melody with pianist Bill O’Connell" (Glenn Astarita, DownBeat). ".. bill connors is about the guitar... yes ... but this album is about much more than guitar... you have to listen to these tracks more than once to experience the depth. connors shines when soloing... and o'connell hangs right with him. just catch the piano solo on 'mind over matter' ... they are pushed by plainfield who can groove yes... and stop on a dime ... shifting gears so seamless... he is incredible... ... one fact about 'return' and connors... the effects and processors for guitar are not there.. only pure tone of the Gibson L5 played through an amp crafted by connors himself... pure smooth tone... best displayed on the track 'try tone today'... ... it is all good... and then there is coltrane's brasilia.. oh my! so sweet" (dr. mike, February 17, 2005, RadioJazz.com). "Connors soars effortlessly through Latin-tinged numbers, funk-tinged blues, and his personal forte, elegant ballads, all conjoined by the shimmering, glasslike tone of his Gibson L5 lines and melodies. Pretty close to exquisite" (Jim Miers, Buffalo News). "Connors takes back seat to no one as a killer jazz guitarist, having won his spurs for his pioneering work in the original Return to Forever line up. Coming back after sometime away from recording, Connors makes the kind of date that used to be routinely issued by the majors when they still cared about music. Having the admiration of his peers, Connors is free to pursue his vision and he never abuses the fan's trust along the way. Dazzling set sure to be a staple on all the year end best lists come December" (Chris Spector, Midwest Record Recap, Vol. 28, number 7, February 14, 2005). Connors is "back with an album that finds him in fine form with a completely unaffected and warm, big-bodied sound. Return has enough energy and groove to appeal to fusion fans but, without the bombast that is so often pegged with that genre, a more direct and economical approach that will appeal to those of a more purist persuasion... [Connors] retains that same sense of thrift, capable of lightning runs when necessary but always constructing solos that make sense and are more than simply a series of notes strung together. Return is, indeed, a welcome comeback from a guitarist whose reputation has never been less than stellar, even though he's never achieved the same level of stardom as some of his contemporaries" (John Kelman, all-about-jazz, 2/18/2005). "Guitarist Bill Connors wouldn't blame you for thinking that he's dead. Thirty years after bursting onto the burgeoning jazz-rock fusion scene with Chick Corea's Return to Forever, Connors is relaunching his recording career with his first release - Return (Tone Center) - since 1987's Assembler... 'I got motivated to get away from the music scene in the early '90s', said the 55-year-old Connors... 'I went through a real Wes Montgomery period in my teens when I was first discovering jazz... In a way, working with my students helped me get back to that because I was doing jazz transcriptions for them and listening to Bill Evans and Trane, stuff that I've always admired'. As a self-taught teenaged guitarist in Los Angeles, Connors went from delving into Montgomery and Django Reinhardt into attempting to meld the power of his favorite saxophonists with Eric Clapton's sweet tone. 'I wanted to get that big sound that Trane and Sonny Rollins got through amplified volume but integrate those singing lines that Clapton played'. His search led him to work with Mike Nock and Steve Swallow in San Francisco and then to an audition with Corea, who was looking to launch an electric quarter. 'Chick was like a god to me, so this was an incredible opportunity'. Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy garnered rave reviews, and Connors quickly assumed his place alongside John McLaughlin and Larry Coryell as electric guitar hero. His decision to quit the band after only a year and eschew electricity on three subsequent recordings for ECM stunned his fans. Looking back over three decades he's at a loss to explain the move. 'Maybe I should've just taken a few days off. It was a little rash'. But Connors isn't a man to harbor regrets. Instead, he looks back on his decision to pursue classical guitar studies in the late '70s as an opportunity to learn more about guitar music, and his experiments with acoustic fingerpicking as necessary to convince him that plectrum playing is his natural métier. The only thing that rankles about his decision to leave fusion behind is that his seminal role was forgotten by the time he returned to electric music the '80s with Step It, Double Up and Assembler. 'I don't have a huge ego, but it still hurt when people would tell me that I must've listened to a lot of Al Di Meola (who replaced Connors in Return to Forever),' Connors said. 'I was robbed of my identity, that my guitar was like a credit card that had been stolen and I'd been left to play the bill'... Although Connors isn't sure Return will lead to more recordings, he's enthusiastic about performing again and thinks he's back on the scene to stay. 'Music is not so mysterious now. I had a lot of impulses to try different things when I was young, but I'm more aware now of what I like', he said. 'I'm more into content and feel than volume. I don't play loud any more. It's all about whether the music is swinging'. (James Hale, DownBeat, April 2005). A 2011 review of Connors' playing on Forever offers more praise: "Bill Connors’ playing on this recording sounds just as fresh as it did in the mid-‘70s" (Jon Liebman, review of Forever, For Bass Players Only, September 2011).

4 comments:

LINK

P/W is aoofc

I still haven't released my solo album, and it's taken a lifetime to do. I understand the music has been linked with cancer of the earlobe, and testicular reflux.

Oh, and thanks for this music too.

RatsoRat (the subzero rodent)

G'day,ratso. Stop listening to One Direction and Little Mix. Your health will improve! Keep those gonads warm. I got inoculated against Weil's disease in a former job (no offence), but some of those varmints can cause a lot of damage to your goolies! Stay cool, & TTU later, old china!....Paul

Thanks

Post a Comment