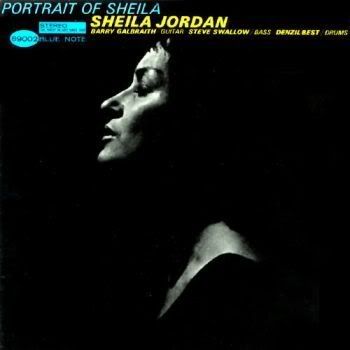

Sheila Jordan - Portrait Of Sheila - 1962 - Blue Note Records (USA)

To quote the Rolling Stone Record Guide, - " Sheila Jordan is, historically and emotionally, one of the finest jazz singers extant." They gave this debut album a 5 star rating. It remains her definitve album, and arguably her best recording. It includes her classic version of "Baltimore Oriole." Buy her sperb album, "Jazz Child. For a taste of the same vocal style, try and listen to the great album, "Steal the Moon," by Carolyn Leonhart, one of the great modern day jazz vocalists.

TRACKS

1. Falling in Love With Love (2:31) Composed by Richard Rodgers

2. If You Could See Me Now (4:32) Composed by Tadd Dameron

3. Am I Blue (4:12) Composed by Harry Akst

4. Dat Dere (2:43) Composed by Bobby Timmons

5. When the World Was Young (4:43) Composed by Johnny Mercer

6. Let's Face the Music and Dance (1:14) Composed by Irving Berlin

7. Laugh, Clown, Laugh (3:11) Composed by Sam M. Lewis

8. Who Can I Turn To? (3:21) Composed by Alec Wilder

9. Baltimore Oriole (2:34) Composed by Hoagy Carmichael

10. I'm a Fool to Want You (4:55) Composed by Frank Sinatra

11. Hum Drum Blues (2:15) Composed by Oscar Brown, Jr.

12. Willow Weep for Me (3:28) Composed by Ann Ronell

MUSICIANS

Sheila Jordan (vocals)

Barry Galbraith (guitar)

Steve Swallow (bass)

Denzil Best (drums)

Recorded at the Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey on September 19 and October 12, 1962.

REVIEW

Sheila Jordan's debut recording was one of the very few vocal records made for Blue Note during Alfred Lion's reign. Accompanied by the subtle guitarist Barry Galbraith, bassist Steve Swallow, and drummer Denzil Best, Jordan sounds quite distinctive, cool-toned, and adventurous during her classic date. Her interpretations of Oscar Brown, Jr.'s "Hum Drum Blues" and 11 standards (including "Falling in Love With Love," "Dat Dere," "Baltimore Oriole," and "I'm a Fool to Want You") are both swinging and haunting. Possibly because of her originality, Sheila Jordan would not record again for over a dozen years, making this highly recommended set quite historic. © Scott Yanow, All Music Guide

BIO (Wikipedia)

Sheila Jordan (born Sheila Jeanette Dawson November 18, 1928 in Detroit, Michigan) is an American Jazz singer and songwriter. Sheila Jordan grew up in Summerhill, Pennsylvania before returning to her birthplace in 1940/41 playing the piano and singing semi-professionally in Detroit clubs. She was influenced by Charlie Parker and was part of a trio called Skeeter, Mitch and Jean (she was Jean) which composed lyrics to Parker's Arrangements. Sheila also claimed in her song "Shelia's Blues" that Charlie Parker wrote the song, "Chasing the Bird" for her, as she and her friends were known to chase him around the Jazz Clubs in the 40's. In 1951 she moved to New York and started studying harmony and music theory taught by Lennie Tristano and Charles Mingus. From 1952 to 1962 she was married to Charlie Parker's pianist Duke Jordan. In the early 1960's she had gigs and sessions in the Page Three Club in Greenwich Village and was working in different clubs and bars in New York. In 1962 she was discovered by George Russell who did a recording of the song "You Are My Sunshine" with her on his album Outer View (Riverside). Later that year she recorded the Portrait of Sheila album (recorded in September 19th and October 12th, 1962) which was sold to Blue Note. Later in the decade she sang jazz liturgies in different churches such as Cornell and Princeton, NYC. Jordan played with Don Heckman (1967-68), Lee Konitz (1972), Roswell Rudd (1972-75) and began her long working relationship with Steve Kuhn around this time. In 1974 she was "Artist in Residence" at the City College and was teaching there in 1975. On the 12th of July 1975 she recorded "Confirmation". One year later she did the duet album simply called Sheila with Arild Andersen (Bass) for SteepleChase in the end of 1976. In 1979 she founded a quartet with Kuhn, Harvie Swartz and Bob Moses. During the 1980's she was working with Harvie Swartz as a duo and played on several records with him. Until 1987 she worked in an advertising agency and recorded Lost and Found in 1989. Sheila Jordan is also a songwriter and is able to work in both bebop and free jazz. In addition to the musicians referred to, she has recorded with the George Gruntz Concert Jazz Band (TCB, ECM), Harvie Swartz (MA Recordings), Cameron Brown, Carla Bley (Escalator over the Hill) and Steve Swallow (Home). In addition to Blue Note, she has led recordings issued by Eastwind, Grapevine, SteepleChase, ECM, Palo Alto, Blackhawk and Muse.

MORE ARTIST INFO © Charles L. Latimer

"Bebop is with me from the time that I get up in the morning until I go to bed at night. I believe that I even dream about it,” says vocalist Sheila Jordan, now 75 years old. “That is how much I’m dedicated to this music.”

Although a bebopper at heart, Jordan has performed with musicians as diverse as trumpeter Don Cherry, vocalist Carla Bley, pianist Don Pullen and trombonist Roswell Rudd. Since gaining recognition with her 1962 Blue Note release “Portrait of Sheila”, Jordan’s crafted a vocal style unrivaled by her peers.

Jordan’s voice is as delicate as a Bee making love to a flower. Her voice drips off your ears like warm honey off a spoon. She prefers to work with only a bassist, a format avoided by most singers; it leaves the two musicians exposed and very much on there own, but Jordan has always thrived on challenge. “I like the sound of that string instrument,” she states. “I like the feeling of freedom that I experience while singing with the bass. I always liked working off that sound.”

Bebop captured her soul in 1947 when Dawson (her father’s surname, although Sheila never knew him), a sophomore at Cass Technical High School, heard one of Bird’s recordings in a hamburger joint near the high school.

“The place had a little jukebox. On it I heard Charlie Parker and his Re-boppers. It wasn’t called be bop yet. I said, ‘oh my God!’ I was always a singer from when I was a tiny little kid. But I never knew this was the kind of music that I wanted to do until I heard Bird.” Parker’s music became her obsession; Jordan forged a fake birth certificate to gain entry into Detroit’s many nightspots, like Club Sudan, that featured the ‘new music’. She met some of Detroit’s premier young musicians, like Tommy Flanagan, Kenny Burrell and Barry Harris and two vocalists, Leroy Mitchell and William “Skeeter” Speight, who became lifelong friends. Mitchell, who became Jordan’s mentor, recalls their first meeting at a neighborhood club.

“We were scatting along with the tunes, and over in the corner was this little white girl scatting. I was shocked because back then…most of the black musicians couldn’t follow along with those Bebop tunes. But Sheila was unique. She came across as one of those white people that were sorry they were white. But she was very hip – she got that from hanging around us! She made a special effort to speak like all the beboppers. One night at the Blue Bird Inn she was talking jive to my wife, and afterward my wife told me that she couldn’t understand a thing that Sheila was saying!” Mitchell recalls.

Mitchell says that Jordan wasn’t a good singer, at first. She had tonality and phrasing problems, and often sang off-key. But she had a solid sense of rhythm, a prerequisite for any jazz musician or vocalist. Mitchell knew Jordan would make a name for herself because of her determination.

In 1948 Mitchell, Jordan and Speight formed a vocal trio they called Skeeter, Mitchell and Jean, a kind of forerunner to Lambert, Hendricks and Ross. They performed Bebop tunes with lyrics added by Skeeter and Mitchell. Although they never gigged on their own, the trio was well known among Detroit musicians and often sat in. Their love for “the music” kept them together for a couple of years.

As a single white female performing with two African American men, Jordan was subjected to harassment and prejudice. Sheila had black friends since she was a small child. “I was comfortable with Afro-Americans because I understood how they thought. I understood how they felt, and I understood the struggles they went through,” she recalled. Detroit was strictly segregated and mixing of the races was taboo. Most African Americans lived in the near east side enclave known as “Black Bottom”. The Detroit Police Department was nearly all white, and blacks were subjected to brutality at the whim of cops patrolling in their neighborhood.

But the Police weren’t the sole perpetrators of bigotry, or violence. Skeeter Mitchell recalled when their trio sat in at the Latin Quarter one night and got a very hostile reaction.

“Most people walked out on us when they discovered that a white girl was signing with two black guys,” he said. “Most of the people in the audience were white.” This would not be their last encounter with bigots and racist cops. Mitchell says Jordan received the brunt of the hostility. “I went through a lot with the music because it was very prejudiced in Detroit back then. Being white you know I was constantly at the police station. They were always taking me down questioning me because I was hanging out with my black brothers and sisters,” Jordan recalls.

Her history in black and white

Although born in Detroit (on November 18, 1928), Jordan spent her first twelve years with her maternal grandparents in a poor Appalachian coal-mining town in Pennsylvania. As a youngster she hung out with the black kids in her Pennsylvania neighborhood. She experienced prejudice because her family was the poorest family on the block, with a history of alcoholism, to boot.

She rejoined her mother in Detroit at age thirteen. Jordan only stayed there for two years; her mother was an alcoholic, and was married to an abusive husband. Jordan moved into a girl’s home. She first attended Cass Technical High School, then transferred to, and graduated from, Commerce High School, a clerical trade school. Although the school was integrated, Jordan was an outcast because she socialized with the black students. “The principal of the school called me down to her office one day. She said…’you look nice and dress nice, so why do you hang out with all the black girls?’”

Romance & Rhythm

At age twenty Jordan met a handsome twenty-year old tenor saxophonist named Frank Foster at the Blue Bird Inn. They quickly developed strong feelings for each other and fell in love. They lived together until Foster was drafted in 1951.

Their relationship made her more of a target for the Police. The bigotry started to unnerve her. She recalls the incident that convinced her to leave Detroit. “I was with Frank. It was Frank and I and my friend Jenny and her date. The cops stopped us. I was smoking a cigarette before they stopped us, and I flicked it out the window. They thought it was dope. One cop literally crawled under the car to get it. They took us down to the police station and interrogated us. They put the guys in a different cell. This plainclothes cop looked me in the eyes. He had the coldest eyes that I have ever seen in my life. He said that he had a young daughter at home, and that if he thought that he would find her the way that he found me tonight that he would take out his gun and blow her brains out. That is what he said. I remember saying to myself that I had to get out of this city. I couldn’t take it anymore.”

Foster went to fight in Korea, and Jordan moved to New York. Ever the optimist, she believed things would be better for her racially – and musically. “I went to New York for two reasons,” she recalled. “One, I was chasing Charlie Parker. I was totally mesmerized by him…totally addicted to Bebop. I needed to be around Bird. I also left because of the prejudice,” she added.

Typist by day, bebopper by night

Once in New York, she got a day job as a typist at an advertising agency. She shared an apartment with her friends Jenny King and artist Virginia Cox. On Monday and Tuesday nights Jordan performed at a gay bar in the Greenwich Valley called the Page Three. There she worked with pianist Herbie Nichols and bassist Steve Swallow. Nichols, a true jazz original, was, like Jordan, a brilliant musician who never attracted a mainstream following. His style was audacious and his harmonic sense highly developed; only a vocalist with a quick ear could appreciate Nichols. Jordan met bassist Charles Mingus, and drummer Max Roach. Mingus introduced her to pianist Lennie Tristano, and she studied with Tristano for three years. He helped Jordan improve her phrasing by listening to Parker and Lester Young solos. He also instilled in Jordan the importance of following one’s own path in life. “What I learn from Lennie more than anything else…was the ability to be more of myself, and not to worry because I didn’t have this fantastic voice. He told me that I could do anything as long as I stayed true to myself and didn’t force improvisation, and to learn as many good songs as I could,” Jordan says.

She moved from the shared apartment to a loft in Manhattan on 26th Street that became a popular spot for late-night jam sessions. Life was good; she hung out with Parker regularly, going to his gigs and often sitting in; Bird would introduce her as “the singer with the million dollar ears.” Bird, too, had golden ears, and he knew an original sound and style when he heard one. Jordan’s loft became a safe haven for Parker. He used to bring over stacks of classical albums that they listened to for hours. “There wasn’t anything romantically happening between us,” she said. “I just loved him and loved his music.”

Jordan married Parker’s former pianist Duke Jordan, whom she’d met in Detroit during a Parker Quintet engagement; she joked that she married Duke to be closer to Parker. They had met in Detroit when he came to town with Parker. She jokes that she married Duke to be closer to Parker.

Unfortunately, the bigotry she’d hoped to avoid in life resurfaced. One night she’d left her loft with two black friends when three white men attacked them, one of whom brandished a gun. Jordan’s front teeth were kicked out in the ensuing beating. The incident marked the start of a slow downward spiral for Sheila Jordan. Duke’s drug use increased, and he split after their daughter Traci was born. Worse, her dear friend Charlie Parker was steadily deteriorating.

“I was with Bird the night that they turned him away from Birdland. They wouldn’t let him in because of the way that he was dressed. He had on t-shirt that was soiled. He was so hurt. He turned to me and said, ‘can you believe that they won’t let me into the club that they named after me?’ We went to a penny arcade after being turned away.” Bird, too, was on a downward spiral; he died a few months later, at 34. Jordan finally divorced Duke in 1957. She continued working as a typist, and at night performed at Page Three.

New beginnings and habits

It was during her Page Three performances that Jordan’s style took shape. She met composer/pianist George Russell and Blue Note Records founder Alfred Lion, two men who recognized her distinct sound & style and gave her career a boost. Jordan worked with pianist Jack Reilly, a student of Russell’s, who brought Russell to the club one evening. “Sheila’s voice had an authenticity to; it reflected all her life experiences,” Russell said of Jordan’s singing. Impressed with Jordan, Russell used her on his album The Outer View. She sang a memorable version of You Are My Sunshine.

Russell got the idea to record the song while accompanying Jordan on a visit to her hometown.

“Sheila took me to an economically devastated area of Pennsylvania to meet her grandmother; upon our arrival, her grandmother took us to the local beer garden where the unemployed mine workers were passing the time. There was an old piano, and Sheila was asked to sing, with me accompanying her. The miners didn’t like our choice of music, and told us to do something familiar. We did ‘Sunshine,’ which planted the idea of the version, which I arranged for ‘The Outer View’,” Russell recalled.

He helped Jordan helped record a demo, which he then shopped around to various record labels, including Blue Note. Alfred Lion’s wife Ruth, also a vocalist, knew of Jordan and had told Lion about Jordan, but Lion hadn’t made it to Page Three for a Jordan performance. After hearing her demo, he went to hear Jordan.

“Alfred told me that he like the performance. A few weeks later George told me that I had a record date. George was more or less representing me then,” Jordan said. At that time (1962) Blue Note was recording only instrumentalist like Hank Mobley, Horace Silver, and Art Blakey, not vocalists. Jordan became the first female vocalist to record for the label. “A Portrait Of Sheila”, used a trio comprising drummer Denzil Best, guitarist Barry Galbraith and Steve Swallow, her friend and longtime bassist. Jordan initially wanted to use only bass, but Russell convinced her that a larger group was a better showcase for her voice.

The album received favorable reviews, and Down Beat magazine voted her vocalist more deserving of wider recognition. “A Portrait Of Sheila” was the only album Jordan made for Blue Note. It became a classic, but it didn’t jumpstart her career. Jordan didn’t have an agent. Raising her daughter and working full-time didn’t leave her much time to solicit gigs. Jordan’s style and sound didn’t have the widespread appeal of vocalists like Sarah Vaughn, June Christy, Carmen McRae and Anita O’Day. In fact, Jordan’s career stalled, and she started drinking heavily. Club Patrons would buy her drinks. She refused, at first, but found that one or two drinks made her feel better about herself. “(At first) I would pretend like I would swallow the drinks, but I would spit it back into the glass,” she said. “Eventually I started drinking it little by little.” Those little sips turned Jordan into an alcoholic. She made attempts to straighten up, but she endured eight years of hell before finally quitting for good in 1978. Recovering from a drinking binge she had an epiphany. “I had a spiritual awakening…I saw this message and it said, ‘I gave you a gift and unless you respect it and take care of it, I’m going to take it away from you and give it to somebody else.’ I said, ‘WHOA!’” Jordan hasn’t had a drink since. She joined Alcoholics Anonymous, and has been sober for twenty-six years.

Second chances are the best

Since she’s been sober, Jordan accepted a buyout package from the Advertising agency and has been working full time as a jazz singer. “My whole musical life changed,” she recalled. “I started working all the time. I’m 75-years-old and I’m working in places that I never dreamt I would be working in.” She started working in other jazz clubs in New York such as Birdland, Village Vanguard, and the Blue Note. Jordan’s very much in demand on the national and international festival circuit. She’s been a featured attraction at jazz festivals in Austria, Czechoslovakia, England, Italy and Japan. Jordan also began teaching music at City College Of New York; she’s still on the faculty. Word of her teaching prowess spread, and Jordan is now a visiting professor at the University of Massachusetts and Stanford University. In 1995 filmmaker Cade Bursell made a documentary about Jordan titled “Sheila Jordan: In the Voice of A Woman”. The same year she was honored in Detroit with a lifetime achievement award from the Societie of the Culturally Concerned, one of many such awards she’s received.

Jordan’s recording activities increased. As a leader she recorded a string of outstanding albums like Heartstrings, Lost and Found, The Crossing, Body and Soul, Sheila, and Confirmation. But her several duet LPs with bassist Harvie Swartz gained her the most recognition.

“I worked very hard to be able to play this music because I love it, and I believe in it. I knew from the get go that I got the inspiration to do this music to put my feeling and emotions, my life experiences into it from other jazz musicians. But I think that the music is too important to bring all the hatred that I experienced into it,” Jordan says.

After 60 years of boppin’, scattin’ and singin’, Jordan still has the same hunger and enthusiasm to perform and record the music that transformed her life. And that’s a blessing for us all.

Final thoughts…

Sheila Jordan’s style and sound are unique. She bends, shapes and changes words/sounds to express what she’s feeling; Jordan is the purest jazz singer on the scene today. Jordan puts a lot of feeling into each song, but her straight bebop scatting is a wondrous thing to hear. © www.detroitmusichistory.com/Shelia.html

4 comments:

Bad link - mass mirror fails to open.

LINK

Hi! Anonymous. Try link above, and please let me know if you have any problems...Thanks

thanks for

Sheila Jordan - Portrait Of Sheila

Hi,rje. And I thank you for your interest and comment. Please keep in touch

Post a Comment